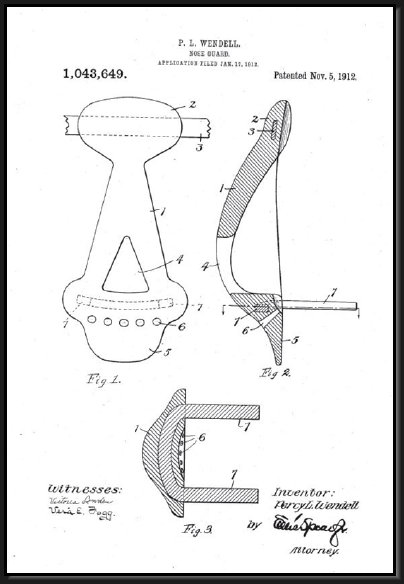

The Wendell Nose Mask

In 1912, Percy Langdon Wendell, the "Famous line bucker and Captain of Harvard's 1911 Foot Ball Team," invented a mask that protected the nose and reduced the risk of damage to the front teeth. Wendell's design replaced the rubber mouthpiece with two strips of leather that were gripped between the wearer’s side teeth. According to Wendell’s 1912 specification in support of U.S. Patent No 1,043,649, not only did his guard reduce the “strain and shock” to the front teeth, it also allowed for “breathing through the mouth without raising the mask.” The Wendell Patent Nose Mask first appeared in the 1912 Spalding Football Guide as the No. W (regulation size) and the No. WL (extra-large size) and continued to be listed for sale for $0.50 through the mid-1920’s. The Wendell Mask came to market as nose mask popularity waned. As a result, few examples of the No. W survive today.

Circa 1912-1923 Wendell Nose Mask

Legendary Auctions, August 2008

Legendary Auctions, August 2008

Patent Illustration, Patent 1,043,649 “Nose Guard”

P.L. Wendell,submitted January 17, 1912

P.L. Wendell,submitted January 17, 1912

The Nose Protector Head Harness

While not mandatory in college football until 1939, the vast majority of football players wore helmets by the mid-1920's. This gave equipment manufacturers the opportunity to devise a variety of nose protection devices that were incorporated into or worn in tandem with helmets. In 1921, P. Goldsmith & Sons introduced the first helmet with an integral leather nose guard, the No. 64 Nose Protector Head Harness. By the mid-1920's, Spalding, Rawlings, Reach, Draper-Maynard and other manufacturers were producing their own variations of the nose protector helmet.

By the late 1930's, fibre-reinforced leather helmets afforded enough rigidity for rubber covered steel face masks to be attached directly to helmets. A variety of shapes and sizes of "face and nose guards" were offered by sporting goods manufacturers, with most being produced by third party suppliers. These face masks were purchased separately from the helmet, allowing player's to select the style of mask most suited to their game. By the late 1940's, helmets with integral facemasks were introduced, however, these would not become standard equipment on the football field until the 1960's.

1941-1942 Rawlings Football Catalog, image courtesy of Ron Robert.

Goldsmith No. 64 - Goldsmith 1925 Catalog

Goldsmith Executioner Helmet, circa 1921

Questions or comments? Email me at:

New York Giants Player with rubber covered steel Face & Nose Guard attached to a leather wingfront helmet, 1938

Nose Guard Ad, Draper & Maynard Fall & Winter Catalog for 1936-37.

Visibility restrictions and discomfort limited the popularity of nose protector head harnesses. However, as with their rubber predecessors, they found a niche with players with pre-existing injuries. Rather than purchasing a relatively expensive nose protector helmet after an injury, players could also purchase a standalone nose guard, such as the Spalding No. NP, which could be worn in tandem with their own helmet. These masks were constructed of a leather-encased, rigid fiber board that was "designed that it will not flatten out no matter how hard a blow the player may receive on nose," and was attached to the head with adjustable leather straps.

c. 1926 Spalding No. NP Nose Protector

No. NP Nose Protector Ad, 1927 Spalding Catalog

Draper & Maynard No. NG2, circa 1937

Draper & Maynard No. NG1, circa 1935

The History of the Football Nose Mask

Football's Most Unusual Protective Device

Chris Hornung

March 10, 2015

Updated July 2, 2017

Page 4

March 10, 2015

Updated July 2, 2017

Page 4

Between 1900 and 1905, at least 45 football players died from injuries suffered in what was quickly evolving into a violent, dangerous game. In response, President Theodore Roosevelt called upon the representatives of the nation’s leading institutions, Harvard, Yale, and Princeton, to amend the rules of the game to improve player safety. The “Official Foot Ball Rules of 1906” instituted key changes that minimized and eliminated many high impact collisions. The new rules established the fixed line of scrimmage, the neutral zone, and the forward pass. They also eliminated wedge blocking techniques and pre-snap forward motion. New rules governing foul play were added as well. Rule 22.(b) stated:

There shall be no striking with the fist or elbows, kneeing, kicking, meeting with the knee, nor striking with the locked hands by line men, when they are breaking through; nor shall a player on defense strike in the face with the heel of the hand, the opponent who is carrying the ball.

NOTE – The Committee further recommends that a player who is twice disqualified in the same season for the above offenses, or for a deliberate attempt to injure and opponent, shall not be permitted by the authorities of his institution to play again within one year from the date of the second disqualification.

NOTE – The Committee further recommends that a player who is twice disqualified in the same season for the above offenses, or for a deliberate attempt to injure and opponent, shall not be permitted by the authorities of his institution to play again within one year from the date of the second disqualification.

Over the next decade, these new rules were more uniformly implemented across the country and the style of play became faster and more open. As a result, players more frequently sacrificed nose protection for better visibility and comfort. A faster game also lead to higher speed collisions during which a blow to a nose mask could cause significant damage to a players mouth and teeth. A common sight in team photos from 1895-1915, nose masks are virtually non-existent in post-1915 photographs.