Outlawed: Banned Uniforms of American Football

Chris Hornung

May 3, 2016

May 3, 2016

Team Photo showing Friction Jerseys, circa 1935

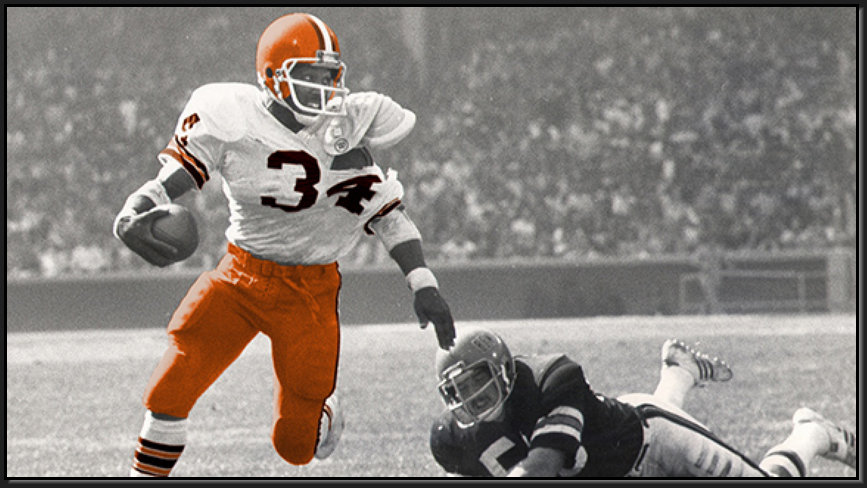

As an All-American at the University of Oklahoma, Greg Pruitt rushed for 3,122 yards and 41 touchdowns. Finishing third in Heisman Trophy voting in 1971 and second in 1972, the diminutive Pruitt possessed a unique combination of deceptive speed and quickness. In a March 2015 interview with www.clevelandbrowns.com, Pruitt described his running style,

A competitive species to the core, human beings are uniquely adept at developing innovative techniques, skills, and materials to increase our advantage. Throughout its 150 year history, American football has been a laboratory for innovation, constantly evolving as teams strive for victory. At times, those innovations have given players advantages deemed to be unfair, and regulating bodies have been called upon to regulate their use. Join us as we look back in history at five banned uniforms of American football.

In March 2015, the NCAA adopted a new rule banning illegal equipment, "such as jerseys tucked under the shoulder pads or exposed back pads," and requiring that "the player leave the field for at least one play," and not be permitted to return until his equipment is corrected. Dubbed the "Ezekiel Elliott Rule," the requirement was primarily directed at the Ohio State running back, whose tucked jersey and exposed abdominals became his calling card during the 2014 season. So why did the NCAA make the "Elliott Tuck" illegal? Did Elliott's tucked jersey provide an unfair advantage by making him more difficult to tackle? Perhaps, but consider this: Elliott and his exposed six-pack accounted for 1,878 yards and 18 touchdowns in 2014, while the more modest Elliott with his midriff covered ran for 1,821 yards and 21 touchdowns in 2015.

Drafted in the second round of the 1973 NFL draft, Pruitt took his tear-aways to Cleveland, where he was selected to the Pro-Bowl in 4 of his first 5 years of professional football. During his career, the Browns equipment manager was one of the busiest staffers on the field, replacing an estimated 4 or 5 Pruitt jerseys per game. While not the only player to use tear-away jerseys in the college and professional ranks, Pruitt was the most high-profile, so much so that in 1979 the NFL adopted the "Greg Pruitt Rule," banning the tear-away jersey. Pruitt may be the only professional football player to have had his jersey retired 5 years before the end of his career. Pruitt hung up his cleats in 1984 and was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1999.

“My style was elusive,” Pruitt said. “Nobody could get ever get a squared-up, dead, knockout blow on me but they were always reaching and grabbing because of my size."

Unable to catch up with Pruitt, defenders often resorted to "shirt tackling," by grabbing his jersey and pulling the 5'10", 190 lb. running back to the ground. In response to this technique, Pruitt employed the "tear-away" jersey. Introduced by Russell Athletics in 1967, the tear-away jersey was made out of lightweight fabric that would easily rip apart and tear when pulled. Instead of a tackle, defenders were left with a handful of fabric.

40 years prior to the introduction of Russell Athletic's disintegrating jersey, sporting goods manufacturers developed a jersey they claimed would "prevent fumbling." Popular from the mid-1920's until the late 1930's, the friction strip jersey employed thin strips of canvas, leather, or moleskin down the front of the chest and on the inside of the arms. Trademarked as "Grip Sure," "Holdtight," and "Stickum Cloth," the strips provided greater friction than a cotton jersey and aided players in holding the ball tightly. Snugtex, a new friction material developed in the late 1920's, was made of "canvas with rubber threaded through, forming a surface with unequaled holding and gripping qualities."

Friction jerseys were sold in dozens of colors and strip patterns, creating some of the most unique and interesting jersey designs in the history of American football. They were worn by nearly all of the major college and professional football teams between 1925 and 1935. So what happened to this innovative piece of athletic equipment?

The friction jersey's demise came as a result of two factors. First, in the depths of the Great Depression, schools and players sought out cheaper alternatives for their athletic gear. Suppliers began producing jerseys using lower quality materials. Add-ons, such as friction strips that cost up to $0.50 per strip, were deemed non-essential.

Second, in the mid-1930's the NCAA began enacting rules that focused on eliminating equipment that gave players or teams unfair competitive advantages and required standardized uniforms for each team. Not all players could afford the friction strip upgrade to their uniforms making those who wore them non-compliant. By 1940, friction jerseys disappeared from the American gridiron for good.

The friction jersey's demise came as a result of two factors. First, in the depths of the Great Depression, schools and players sought out cheaper alternatives for their athletic gear. Suppliers began producing jerseys using lower quality materials. Add-ons, such as friction strips that cost up to $0.50 per strip, were deemed non-essential.

Second, in the mid-1930's the NCAA began enacting rules that focused on eliminating equipment that gave players or teams unfair competitive advantages and required standardized uniforms for each team. Not all players could afford the friction strip upgrade to their uniforms making those who wore them non-compliant. By 1940, friction jerseys disappeared from the American gridiron for good.

Alex Taylor Football Jersey Advertisement, 1929

In this case, the NCAA's ruling was most likely a continuation of its policies (and struggle) towards maintaining the "amateur ideals" of college athletics. While this notion is somewhat laughable coming from a non-profit organization with more than $1.0 billion in annual revenue, over the past decade the NCAA has been fairly consistent in prohibiting uniform adaptations that are inconsistent with the style worn by the entire team, and/or call attention to an individual player. The league has prohibited individualized equipment such as visible bandanas and headbands, excessively built facemasks, non-compliant gloves and shoes, and messages written on tape or wristbands. In the same vein, the NCAA has adopted rules penalizing actions that draw attention to the the individual, including personalized celebrations, hand gestures, and removing one's helmet on the field of play. Elliott claimed he tucked his jersey for comfort, however, his reported desire to trademark the monikers "Hero in a Half-Shirt," and "In Crop We Trust," represents the type of self-promotion that the NCAA is attempting to squash in college athletics.

Friction Jersey attributed to Washington

& Jefferson College, Circa 1930.

& Jefferson College, Circa 1930.

Getty Images