The Pottsville Maroons'

NFL Legacy

Chris Hornung

August 28, 2017

August 28, 2017

At the 2017 National Sports Collectors' Convention in Chicago, Illinois, an avid early pro-football collector and owner of www.antiquesportsshop.com and was given the opportunity of a lifetime, a chance to own a rare artifact of the "Perfect Football Machine." The 24" tall cup wasn't the stolen 1925 NFL championship whose return Pottsville residents have been waiting for the past 92 years, but the trophy won by the Maroons as champions of the Anthracite Football League the year prior.

Pottsville's 1924 campaign proved that Pottsville's eccentric owner Dr. John "Doc" Striegel, had an effective, albeit controversial, formula for success that would vault the Maroons to the pinnacle of the National Football League the following year. The annulment of their 1925 championship over a dubious, territorial infringement claim was the product of a growing resentment of Striegel's tactics by league titans and his unwillingness to bend the knee to league management. In the end, the Pottsville Maroons' greatest contribution to football wasn't their miraculous string of NFL victories in 1925, but their defeat of Notre Dame, which affirmed that professional football had finally surpassed the college game.

Pottsville's 1924 campaign proved that Pottsville's eccentric owner Dr. John "Doc" Striegel, had an effective, albeit controversial, formula for success that would vault the Maroons to the pinnacle of the National Football League the following year. The annulment of their 1925 championship over a dubious, territorial infringement claim was the product of a growing resentment of Striegel's tactics by league titans and his unwillingness to bend the knee to league management. In the end, the Pottsville Maroons' greatest contribution to football wasn't their miraculous string of NFL victories in 1925, but their defeat of Notre Dame, which affirmed that professional football had finally surpassed the college game.

1920’s professional football teams depended upon gate receipts for their survival, and no player in the country thrilled crowds like Chicago Bears’ rookie, and former Illinois All-American, Red Grange. As the game's biggest star, Grange drew crowds as large as 70,000, generating huge paydays for the Bears and their opponents. Fully expecting to quickly dispatch the upstart Maroons, the Cardinals hoped their victory and championship title would be their ticket to scheduling a rematch against the cross town Bears at Comiskey Park, in what would be an enormously profitable end-of-year matchup.

The Cardinals plans, however, were dashed by a devastating Maroon defensive line that suffocated Chicago ball carriers all day. Pottsville struggled early after its two top running backs fell injured, but found a savior in a diminutive 155-pound third-string half-back, Walter French. Despite playing little all season, French darted through the Cardinals defense with speed and malice, scoring once and setting up another score late in the second half. When the dust settled, the Maroons emerged victorious, 21-7.

Striegel had no time to celebrate; bloated salaries and high travel costs had left the team practically bankrupt. Weeks earlier he had turned down a Frankford challenge to a tie-breaking third game and instead arranged to play the University of Notre Dame's All-Stars at Shibe Park in Philadelphia. Led by the unstoppable "Four Horsemen" backfield, the Fighting Irish had suffered only two defeats in 30 games. Striegel hoped the game would provide desperately needed revenue and perhaps enough notoriety to entice Grange and the Bears to play the Maroons before season's end.

Frankford's owner, Shep Royle, protested the Notre Dame game, claiming it violated an unwritten NFL rule limiting teams from playing within another teams's territory. Fearing a lawsuit by Notre Dame if he backed out of the game, Striegel engaged Royle in peace talks and eventually convinced him to call off his protest. News of the truce was met with raucous celebrations in Pottsville and a mad rush on tickets to the upcoming game. Unfortunately for Striegel, Joe Carr wasn't moved by the detente. Carr faced a difficult decision. On one hand, the game could bring the NFL the national exposure it desperately needed and craved. As much as he might hate to admit it, the Maroons were the class of the league and its best chance of proving the professional game equal to college football. On the other, Carr couldn't allow Striegel to continue to blatantly disregard league rules. He opted to forbid Striegel from playing the game, an order he likely knew Striegel was incapable of following.

The Cardinals plans, however, were dashed by a devastating Maroon defensive line that suffocated Chicago ball carriers all day. Pottsville struggled early after its two top running backs fell injured, but found a savior in a diminutive 155-pound third-string half-back, Walter French. Despite playing little all season, French darted through the Cardinals defense with speed and malice, scoring once and setting up another score late in the second half. When the dust settled, the Maroons emerged victorious, 21-7.

Striegel had no time to celebrate; bloated salaries and high travel costs had left the team practically bankrupt. Weeks earlier he had turned down a Frankford challenge to a tie-breaking third game and instead arranged to play the University of Notre Dame's All-Stars at Shibe Park in Philadelphia. Led by the unstoppable "Four Horsemen" backfield, the Fighting Irish had suffered only two defeats in 30 games. Striegel hoped the game would provide desperately needed revenue and perhaps enough notoriety to entice Grange and the Bears to play the Maroons before season's end.

Frankford's owner, Shep Royle, protested the Notre Dame game, claiming it violated an unwritten NFL rule limiting teams from playing within another teams's territory. Fearing a lawsuit by Notre Dame if he backed out of the game, Striegel engaged Royle in peace talks and eventually convinced him to call off his protest. News of the truce was met with raucous celebrations in Pottsville and a mad rush on tickets to the upcoming game. Unfortunately for Striegel, Joe Carr wasn't moved by the detente. Carr faced a difficult decision. On one hand, the game could bring the NFL the national exposure it desperately needed and craved. As much as he might hate to admit it, the Maroons were the class of the league and its best chance of proving the professional game equal to college football. On the other, Carr couldn't allow Striegel to continue to blatantly disregard league rules. He opted to forbid Striegel from playing the game, an order he likely knew Striegel was incapable of following.

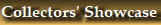

On December 20, 1924, the Pottsville Maroons were crowned champions of the Anthracite Football League at a banquet held at the Allan Hotel in Philadelphia. Doc Striegel accepted the Ray Curran trophy, a massive 24" high silver cup presented by Curran and Meade, a local restaurant. During his acceptance speech, Striegel scorned Frankford for turning down his challenge, a foreshadowing of the hostilities that would set the stage for the politically motivated annulment of the Maroons NFL championship a year later. The highlight of the evening was Striegel's announcement of the signing of ten new players and his intent to seek admission into the NFL for the 1925 season.

In reality, the NFL's decision to admit Pottsville wasn’t altruistic, it was opportunistic. The league's Midwestern and Eastern teams found it costly to travel between these two regions for just one game. A centrally located cupcake ensured the league titans additional gate revenue and an easy victory, padding both their pockets and records on their way home. Since Pottsville didn’t enforce Blue laws which prohibited games on Sundays, teams could follow their Saturday contests with a second game in Pottsville the following day.

Doc Striegel, however, wasn't one to lay down. After his team’s admission, he once again made fast enemies of opposing teams and league management by poaching star players with salaries that were surely unsustainable for a coal town of little more than 20,000 residents. After exhausting his own personal finances, Stiegel relied upon door-to-door fundraisers, and loans from local merchants to keep the team afloat. His gamble worked, for a while. After an early season loss to the Providence Steamrollers, the Maroons destroyed the Canton Bulldogs (28-0), the Columbus Tigers (20-0) and the Akron Pros (21-0). Following a mid-season setback, a road loss to the reviled Frankford Yellow Jackets (0-20), the Maroons finished strong with a huge victory over the Green Bay Packers (31-0) and by exacting revenge on the Yellow Jackets 49-0 at home.

Doc Striegel, however, wasn't one to lay down. After his team’s admission, he once again made fast enemies of opposing teams and league management by poaching star players with salaries that were surely unsustainable for a coal town of little more than 20,000 residents. After exhausting his own personal finances, Stiegel relied upon door-to-door fundraisers, and loans from local merchants to keep the team afloat. His gamble worked, for a while. After an early season loss to the Providence Steamrollers, the Maroons destroyed the Canton Bulldogs (28-0), the Columbus Tigers (20-0) and the Akron Pros (21-0). Following a mid-season setback, a road loss to the reviled Frankford Yellow Jackets (0-20), the Maroons finished strong with a huge victory over the Green Bay Packers (31-0) and by exacting revenge on the Yellow Jackets 49-0 at home.

The 1924 Pottsville Maroons, Doc Striegel far left

Even with an impressive 9-2 record, the Maroons had yet to prove they could win away from the friendly confines of Minersville Park. Their season had featured only two road contests, one of them the humiliating defeat to the Yellow Jackets. On December 6, 1925, the Maroons traveled to the ice-covered gridiron of Comiskey Park to battle the Chicago Cardinals in what was dubbed the “National Professional Football league title.” With temperatures in the 20's, the Maroons weren’t expected to give the 9-1-1 Cardinals much of a fight at Comiskey Park.

River into the "Queen City of the Anthracite." While many grew wealthy, most working age Pottsvillian men toiled brutally long hours in the mines of Sharp Mountain. When they weren't working, they sought refuge in bars drinking Yuengling, the hometown brew, and on weekends, watching football at Minersville Park. By the early 1920's, every respectable blue collar Pennsylvania town fielded a football teams to satiate hard-working residents' longing for entertainment, heroes, and bragging rights. 1920's professional football, however, was a far cry from respectable. As opposed to the college game, professional contests were rife with illegal gambling, lewdness, and public intoxication, and not just by the players.

In the spring of 1924, one of Pottsville's more eccentric, self-confident, and competitive inhabitants, Dr. John "Doc" Striegel, set a course to put the coal town on the national map. The 39 year old surgeon, who was the town's leading physician, had founded Pottsville's A.C. Milliken Hospital after returning from World War I. An avid athlete in his youth, Striegel saw opportunity in the Pottsville football team and purchased a controlling ownership stake in the franchise. With the promise of season-long contracts with unprecedentedly high salaries, Striegel wooed some of the best NFL and college players to Pottsville. This raid upon NFL teams drew the ire of NFL president Joe Carr, a crusader for cleaning up professional football's less than wholesome image. Carr encouraged Cleveland, the aggrieved team, to sue Pottsville, but the lawsuit was quickly dismissed by a hometown Schuylkill County judge. Spurned by the NFL, Striegel entered his team in the newly formed Anthracite Football League, a semi-professional league primarily made up of eastern Pennsylvania coal towns.

A week before the first game, Striegel's team had neither a name nor uniforms. Zacko's Sporting Goods came to the rescue, supplying the team with a surplus box of 25 jerseys that happened to be maroon...and the Pottsville "Maroons" were born. Striegel's band of rough and tumble hometown miners and imported ringers overpowered the Anthracite League competition, earning the moniker, "The Perfect Football Machine." Outscoring their opponents 278-7, the Maroons boasted an 11-1-0 record in their first 12 games. Not only had Striegel's investments lead to lopsided victories, it transformed the residents of Pottsville into the “Coal Crowd,” a rabid, boisterous fan base that packed rocky Minersville Park and traveled in great numbers to opposing teams' stadiums to watch their Maroons. Striegel numerous attempts to schedule a game against the closest NFL franchise, the Frankford Yellow Jackets, were refused. However,he was able to schedule a matchup against another NFL team, the Rochester (NY) Jeffersons, for the Maroons' season finale. Much to Steigel’s dismay, Pottsville fell to the Jeffersons 10-7, but the combination of the narrow defeat and the Maroons' impressive and devoted fan base would help make the case for Pottsville's admission into the National Football League the following year.

In the spring of 1924, one of Pottsville's more eccentric, self-confident, and competitive inhabitants, Dr. John "Doc" Striegel, set a course to put the coal town on the national map. The 39 year old surgeon, who was the town's leading physician, had founded Pottsville's A.C. Milliken Hospital after returning from World War I. An avid athlete in his youth, Striegel saw opportunity in the Pottsville football team and purchased a controlling ownership stake in the franchise. With the promise of season-long contracts with unprecedentedly high salaries, Striegel wooed some of the best NFL and college players to Pottsville. This raid upon NFL teams drew the ire of NFL president Joe Carr, a crusader for cleaning up professional football's less than wholesome image. Carr encouraged Cleveland, the aggrieved team, to sue Pottsville, but the lawsuit was quickly dismissed by a hometown Schuylkill County judge. Spurned by the NFL, Striegel entered his team in the newly formed Anthracite Football League, a semi-professional league primarily made up of eastern Pennsylvania coal towns.

A week before the first game, Striegel's team had neither a name nor uniforms. Zacko's Sporting Goods came to the rescue, supplying the team with a surplus box of 25 jerseys that happened to be maroon...and the Pottsville "Maroons" were born. Striegel's band of rough and tumble hometown miners and imported ringers overpowered the Anthracite League competition, earning the moniker, "The Perfect Football Machine." Outscoring their opponents 278-7, the Maroons boasted an 11-1-0 record in their first 12 games. Not only had Striegel's investments lead to lopsided victories, it transformed the residents of Pottsville into the “Coal Crowd,” a rabid, boisterous fan base that packed rocky Minersville Park and traveled in great numbers to opposing teams' stadiums to watch their Maroons. Striegel numerous attempts to schedule a game against the closest NFL franchise, the Frankford Yellow Jackets, were refused. However,he was able to schedule a matchup against another NFL team, the Rochester (NY) Jeffersons, for the Maroons' season finale. Much to Steigel’s dismay, Pottsville fell to the Jeffersons 10-7, but the combination of the narrow defeat and the Maroons' impressive and devoted fan base would help make the case for Pottsville's admission into the National Football League the following year.

The Evening News, December 20, 1924

1925 Pottsville Maroons